Excerpt from "The Writing of 'The Enemy Within' "

THE STORY BEHIND THE STORY

Script Timeline

Richard Matheson’s story outline, ST #14: April 4, 1966.

Matheson’s revised story outline, gratis: April 22, 1966.

Matheson’s 1st Draft teleplay: April 25, 1966.

Matheson’s gratis rewrite (Revised 1st Draft teleplay): May 19, 1966.

Matheson’s 2nd Draft teleplay: May 31, 1966.

John D.F. Black’s script polish (Mimeo Department “Yellow Cover 1st Draft”): June 6, 1966.

Gene Roddenberry’s rewrite (Final Draft teleplay): June 8, 1966.

Additional page revisions by Roddenberry: June 11 & 15, 1966.

Script Timeline

Richard Matheson’s story outline, ST #14: April 4, 1966.

Matheson’s revised story outline, gratis: April 22, 1966.

Matheson’s 1st Draft teleplay: April 25, 1966.

Matheson’s gratis rewrite (Revised 1st Draft teleplay): May 19, 1966.

Matheson’s 2nd Draft teleplay: May 31, 1966.

John D.F. Black’s script polish (Mimeo Department “Yellow Cover 1st Draft”): June 6, 1966.

Gene Roddenberry’s rewrite (Final Draft teleplay): June 8, 1966.

Additional page revisions by Roddenberry: June 11 & 15, 1966.

|

A script penned by Richard Matheson gave Roddenberry bragging rights among the science fiction community. Matheson had frequently written for The Twilight Zone, including “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” starring William Shatner. On the big screen, Matheson wrote The Incredible Shrinking Man -- based on his own book -- and The Last Man on Earth, a screen adaption of his sci-fi horror novel I Am Legend. He also adapted Jules Verne to the big screen, in the space opera Master of the World, as well as the short stories and poems of Edgar Allan Poe for filmmaker Roger Corman, including House of Usher, Tales of Terror, The Pit and the Pendulum and The Raven.

By 1964, Matheson was scripting tongue-in-cheek horror films for American-International -- such as The Comedy of Terror, again teaming Price, Lorre and Karloff, and 1965’s Die! Die! My Darling! Right before this Star Trek assignment, he scripted “Time of Flight” for Bob Hope Chrysler Theatre. Daily Variety called it “a scary combo of private-eye-tough-guy and sci-fi, well-written by Richard Matheson.” |

In years to come, Matheson would write the screenplays for The Night Stalker, Somewhere in Time -- and Steven Spielberg’s cult TV hit, Duel.

Matheson’s introduction to Star Trek came with an invitation from Roddenberry and Desilu to attend one of the studio screenings of “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” He dropped in for the second of these, on March 8. In the room with him were future Star Trek writers George Clayton Johnson (“The Man Trap”), Paul Schneider (“Balance of Terror” and “The Squire of Gothos”), Oliver Crawford (“The Galileo Seven” and “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”), John Kneubuhl (“Bread and Circuses”), and Meyer Dolinsky (“Plato’s Stepchildren”).

Matheson returned to see the pilot a second time on March 16 (with a handful of other writers who would unsuccessfully try to get their material produced). He said, “I think Gene’s idea was to get all the science fiction writers in the TV and film business to write for the show. But I’m not so sure that worked out the way he had hoped.” (116a)

As for the inspiration behind the story, Matheson said, “I had just looked at Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and immediately saw the potential of using that transporter device for separating the two sides of a person’s character. Having an accident with that offered a good way to study the alternative personality. And it was part of my original concept that he [Kirk] needed that negative element in his personality in order to be a good captain. I think, probably, we’re all mixtures of good and bad. If any one of us was all good, we’d be boring. And leaders have to have that drive and that ambition.” (116a)

Despite Matheson’s impressive credentials, the creative team at Star Trek had mixed feelings about his April 4, 1966 story outline. In an interoffice memorandum to associate producers John D.F. Black and Robert Justman, Roddenberry immediately pointed out the upside, telling his associate producers, “I think this could be a tour-de-force for Bill.” There was no question Shatner would love it, but Roddenberry worried, “Wonder if the NBC censors will allow an attempted rape scene?” (GR4-1)

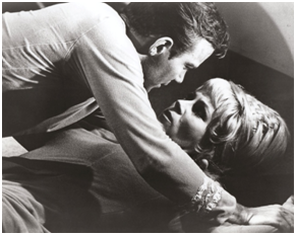

The scene was rendered all the more brutal by Matheson’s description of Kirk’s alter ego. As the “Evil Kirk” wanders the ship, he doesn’t just swill Saurian brandy, he gets downright drunk. He is more barbaric, more reckless and far less cunning than what was ultimately depicted on screen.

It was important to Matheson that the attempted rape be included. It wasn’t part of his story outline merely for exploitation purposes but to enable Kirk’s bad side to take the place of the obligatory science fiction monster. He said, “What else could we show about this side of the Captain that would be more frightening?” (116a)

Attacking and beating a human being, which Kirk’s bad side certainly does, was not enough. A grizzly bear will do that out of instinct. But molestation goes beyond mere survival. It is calculated, even perversely hedonistic. It is the dark side of humanity.

Absent in this first version is the subplot -- that ticking clock -- where the “landing party” is stranded on the planet, sure to perish if Kirk can’t pull himself together in time. Sensing something vital was missing but not sure what, Roddenberry shared with his staff: “Generally, I feel we have a good story here, but I think it may get dull if we let Kirk sit around probing his soul and consulting the doctor about the meaning of all this.” (GR4-1)

Robert Justman did not want the outline sent to NBC. He argued, “This story idea certainly seems to have value to me, but I think in its present form it is rather messy and over-convoluted.... I think we need a revised outline from Mr. Matheson.” (RJ4-1)

Mr. Matheson was agreeable and revised his outline at no charge, turning in version #2 on April 22. The Yeoman being attacked by Kirk was now identified as Rand. Little else had changed. Later that day, Justman wrote to Black, “How do you feel about this story now? I must confess that I am not enthused.” (RJ4-2)

John D.F., however, was. Realizing he was in the minority, his memo to Roddenberry said, “Without meaning to sound facetious, I still like the story; have nothing but confidence in Matheson’s being able to handle it.” (JDFB4-1)

The encouraging word was a moot point. Roddenberry, desperate for scripts and not wanting to alienate someone of Richard Matheson’s status, had already given the go-ahead for him to write his teleplay -- even before hearing from NBC regarding the concept.

Matheson’s first draft script hit Roddenberry’s desk on April 25. New to the story now, at Roddenberry’s insistence, was the subplot dealing with the men left behind on the planet. The leader of those men was not Sulu but a crewman named North.

Matheson’s introduction to Star Trek came with an invitation from Roddenberry and Desilu to attend one of the studio screenings of “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” He dropped in for the second of these, on March 8. In the room with him were future Star Trek writers George Clayton Johnson (“The Man Trap”), Paul Schneider (“Balance of Terror” and “The Squire of Gothos”), Oliver Crawford (“The Galileo Seven” and “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”), John Kneubuhl (“Bread and Circuses”), and Meyer Dolinsky (“Plato’s Stepchildren”).

Matheson returned to see the pilot a second time on March 16 (with a handful of other writers who would unsuccessfully try to get their material produced). He said, “I think Gene’s idea was to get all the science fiction writers in the TV and film business to write for the show. But I’m not so sure that worked out the way he had hoped.” (116a)

As for the inspiration behind the story, Matheson said, “I had just looked at Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and immediately saw the potential of using that transporter device for separating the two sides of a person’s character. Having an accident with that offered a good way to study the alternative personality. And it was part of my original concept that he [Kirk] needed that negative element in his personality in order to be a good captain. I think, probably, we’re all mixtures of good and bad. If any one of us was all good, we’d be boring. And leaders have to have that drive and that ambition.” (116a)

Despite Matheson’s impressive credentials, the creative team at Star Trek had mixed feelings about his April 4, 1966 story outline. In an interoffice memorandum to associate producers John D.F. Black and Robert Justman, Roddenberry immediately pointed out the upside, telling his associate producers, “I think this could be a tour-de-force for Bill.” There was no question Shatner would love it, but Roddenberry worried, “Wonder if the NBC censors will allow an attempted rape scene?” (GR4-1)

The scene was rendered all the more brutal by Matheson’s description of Kirk’s alter ego. As the “Evil Kirk” wanders the ship, he doesn’t just swill Saurian brandy, he gets downright drunk. He is more barbaric, more reckless and far less cunning than what was ultimately depicted on screen.

It was important to Matheson that the attempted rape be included. It wasn’t part of his story outline merely for exploitation purposes but to enable Kirk’s bad side to take the place of the obligatory science fiction monster. He said, “What else could we show about this side of the Captain that would be more frightening?” (116a)

Attacking and beating a human being, which Kirk’s bad side certainly does, was not enough. A grizzly bear will do that out of instinct. But molestation goes beyond mere survival. It is calculated, even perversely hedonistic. It is the dark side of humanity.

Absent in this first version is the subplot -- that ticking clock -- where the “landing party” is stranded on the planet, sure to perish if Kirk can’t pull himself together in time. Sensing something vital was missing but not sure what, Roddenberry shared with his staff: “Generally, I feel we have a good story here, but I think it may get dull if we let Kirk sit around probing his soul and consulting the doctor about the meaning of all this.” (GR4-1)

Robert Justman did not want the outline sent to NBC. He argued, “This story idea certainly seems to have value to me, but I think in its present form it is rather messy and over-convoluted.... I think we need a revised outline from Mr. Matheson.” (RJ4-1)

Mr. Matheson was agreeable and revised his outline at no charge, turning in version #2 on April 22. The Yeoman being attacked by Kirk was now identified as Rand. Little else had changed. Later that day, Justman wrote to Black, “How do you feel about this story now? I must confess that I am not enthused.” (RJ4-2)

John D.F., however, was. Realizing he was in the minority, his memo to Roddenberry said, “Without meaning to sound facetious, I still like the story; have nothing but confidence in Matheson’s being able to handle it.” (JDFB4-1)

The encouraging word was a moot point. Roddenberry, desperate for scripts and not wanting to alienate someone of Richard Matheson’s status, had already given the go-ahead for him to write his teleplay -- even before hearing from NBC regarding the concept.

Matheson’s first draft script hit Roddenberry’s desk on April 25. New to the story now, at Roddenberry’s insistence, was the subplot dealing with the men left behind on the planet. The leader of those men was not Sulu but a crewman named North.

|

“I was a little disappointed that Roddenberry built in a necessity to have a ‘B-story’ about the members of his crew stuck on the planet,” Matheson admitted. “I can see why he did it, because ‘B-stories’ seemed to be a very regular occurrence in television in those days, and maybe still are. But I wanted to concentrate on Bill Shatner’s performance, because he was so good. I had more for him to do in that way. I used to go out of my way to watch Bill Shatner on TV. He was in two of The Twilight Zone episodes I wrote and he was wonderful in both of them --- a very dynamic actor. I didn’t write the script the way I did to challenge him. I wrote it to make it as good as I could. But I was confident Bill could do it.” (116a)

|

Matheson reluctantly added in the B-story, taking care not to let it dominate the tale – one he believed had enough drama in it already. With all of Kirk’s inner angst, creating an outside problem for him to deal with felt artificial to Matheson. Roddenberry disagreed, believing that the men stranded on the planet not only put pressure on Kirk and created an urgency for him to resolve his problems, but tested the Captain, better illustrating the point Matheson wanted to make about the human quality required to make a command decision.

Bill Theiss, looking for costuming ideas, was first to respond to the script, but his memo had nothing to do with wardrobe. Theiss, having worked on the sci-fi sitcom My Favorite Martian, warned Roddenberry:

Bill Theiss, looking for costuming ideas, was first to respond to the script, but his memo had nothing to do with wardrobe. Theiss, having worked on the sci-fi sitcom My Favorite Martian, warned Roddenberry:

|

|

I am apprising you of the fact that My Favorite Martian did a show in which Ray Walston split into three -- negative, positive, and undecided; and another show in which he split into two -- much more to the point of this script, in which the wild half went ‘tom-catting’ off with [actress] Joyce Jemeson and the sober side kept trying to get back together. (BT4)

|

Roddenberry didn’t care about

concepts made silly by My Favorite

Martian and turned his attention to writing a long letter to Richard

Matheson, outlining numerous deep changes he wanted to see in the script. Near

the top of the list was the depiction of Dr. McCoy. Matheson had been writing

the role for Dr. Piper, the character played by Paul Fix in the second pilot

film, the only example of Star Trek

to be seen. Roddenberry wrote:

|

You should have now a copy of the mimeo Writers Information on the ship’s doctor. You will find a cynical “H.L. Mencken” quality which will be most helpful in your script which does use the Doctor considerably. (GR4-2)

|

Roddenberry also didn’t like how Matheson played Kirk’s double as being so primal that he was incapable of being deceitful. He wrote:

|

Suggest some caution in portraying him too animalistic. Let’s keep in mind that even this negative side of Kirk would have our Captain’s intelligence and thus even the most evil things would be done with considerable cleverness. This should help the general blocking of the story too, since the more shrewd and cunning this double, the more of a threat he poses. If he just went drunkenly bumbling around, we’d begin to wonder after a while why our well-trained crew hasn’t been able to apprehend him more easily.... The more I review this aspect, the surer it seems that the double should not be drunk. Let him drink, but does he have to be out and out drunk to be evil? (GR4-2)

|

An important addition to the story was made at this time, with the idea coming from Roddenberry. He told Matheson:

|

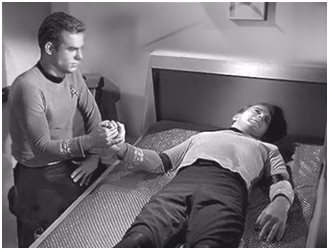

Suggest early in the script, certainly early in Act II, we should begin to suggest that the real Kirk has been changed by all this too. Deprived of the negative side... he must begin to lose some of the strength that positive-negative gives a man. Decisiveness would be one of the first things he’d have trouble with. And he would probably have some difficulty making decisions that endangered others, i.e., the men left down on the planet surface. If his alter-ego is bad and disdainful of the life and safety of others, the real Kirk would possibly be over-conscious of the safety and comfort of others. Important, however, his intelligence would tell him something is wrong and he would struggle against all of this.... In other words, this allows us to display the problems the real Kirk is fighting, but keeping him something of a hero figure even in this strange state since he will be making a valiant fight to stay in command of himself. (GR4-2)

|

Roddenberry also suggested that Kirk not allow himself the prerogative of letting the crew in on his dilemma. He knew from his own experience in the military that in order to lead a leader can never be seen as weak in the eyes of his subordinates. This would be one more weight on the strained shoulders of the tormented Captain.

These suggestions and more infused the story and character elements with the concepts and themes that elevate “The Enemy Within” to classic status. It was no longer just an outer space version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

This was a sizable rewrite to be ordered from a freelancer who had already provided two story outlines before going to script, especially since this rewrite was being provided for free. As such, it was regarded as a Revised First Draft, instead of a 2nd Draft, so Matheson still had one final version he was contractually obligated to deliver and, finally, be compensated for. Gene Roddenberry, as all the Star Trek writers would learn, was a perfectionist who lived by the credo “Scripts aren’t written, they’re rewritten.”

Matheson later said, “Roddenberry had a specific attitude toward the writing of the show. It had to be maintained or he wasn’t satisfied. Rod Serling, on the other hand, was very open-minded. I mean, he was a writer himself. I guess Roddenberry was a writer, too, but Rod did not have any compulsion to impose his own way of thinking on the other writers. He did his scripts for The Twilight Zone as social commentary, which Chuck Beaumont and I never did, and he never said anything about that. He let ours be different.” (116a)

Of course The Twilight Zone was an anthology series with no recurring characters or sets, an entirely different kettle of fish.

It wasn’t until Roddenberry sent his letter to Matheson that NBC, still unaware that a script had been written, finally responded to the story outline. Jon Kubichan, speaking for Broadcast Standards, gave his okay to “go to script” with one very big stipulation “that the scenes between Janice and Kirk’s double be tempered in such a means as to make them acceptable both to NBC and the NAB [National Association of Broadcasters] Code.” (JK4)

The next day, NBC production manager Stan Robertson, also having only read the revised story outline, told Roddenberry: “Our primary concern with this outline in its present form is... the effect upon the viewer that Kirk’s ‘alter ego,’ as outlined here, might have.” (ST4-1)

Matheson’s revised first draft teleplay, meanwhile, was already underway. When delivered on May 19, Roddenberry seemed somewhat content. His memo to John Black and Robert Justman said:

These suggestions and more infused the story and character elements with the concepts and themes that elevate “The Enemy Within” to classic status. It was no longer just an outer space version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

This was a sizable rewrite to be ordered from a freelancer who had already provided two story outlines before going to script, especially since this rewrite was being provided for free. As such, it was regarded as a Revised First Draft, instead of a 2nd Draft, so Matheson still had one final version he was contractually obligated to deliver and, finally, be compensated for. Gene Roddenberry, as all the Star Trek writers would learn, was a perfectionist who lived by the credo “Scripts aren’t written, they’re rewritten.”

Matheson later said, “Roddenberry had a specific attitude toward the writing of the show. It had to be maintained or he wasn’t satisfied. Rod Serling, on the other hand, was very open-minded. I mean, he was a writer himself. I guess Roddenberry was a writer, too, but Rod did not have any compulsion to impose his own way of thinking on the other writers. He did his scripts for The Twilight Zone as social commentary, which Chuck Beaumont and I never did, and he never said anything about that. He let ours be different.” (116a)

Of course The Twilight Zone was an anthology series with no recurring characters or sets, an entirely different kettle of fish.

It wasn’t until Roddenberry sent his letter to Matheson that NBC, still unaware that a script had been written, finally responded to the story outline. Jon Kubichan, speaking for Broadcast Standards, gave his okay to “go to script” with one very big stipulation “that the scenes between Janice and Kirk’s double be tempered in such a means as to make them acceptable both to NBC and the NAB [National Association of Broadcasters] Code.” (JK4)

The next day, NBC production manager Stan Robertson, also having only read the revised story outline, told Roddenberry: “Our primary concern with this outline in its present form is... the effect upon the viewer that Kirk’s ‘alter ego,’ as outlined here, might have.” (ST4-1)

Matheson’s revised first draft teleplay, meanwhile, was already underway. When delivered on May 19, Roddenberry seemed somewhat content. His memo to John Black and Robert Justman said:

|

Like this story very much. Dick has done a good job and it should make a good episode. With some “hypoing” of the perils, both emotional and physical, with some thought and work on increasing the moments of suspense, it could become an outstanding episode. (GR4-3)

|

One aspect that Roddenberry felt needed “hypoing” was the character of McCoy, feeling that the yet-to-be-seen ship’s doctor was portrayed too much like Gunsmoke’s “Doc” instead of like “H.L. Mencken, the curmudgeon, the sharp-tongued individual,” and that the dialogue written for McCoy did not have enough “bite.” Roddenberry also felt Matheson was not utilizing the Spock-McCoy relationship as established in the sample scripts provided, and had not understood “that the two men don’t get along too well.” (GR4-3)

He told Black and Justman:

He told Black and Justman:

|

As written now, despite Dick’s well-known ability at dialogue, many scenes in this script lack the spice and excitement of individual strong personalities and the conflict of distinct and separate ideas and attitudes on life, medicine, discipline, etc. Too often they are simple exchanges of information, admittedly well done, but without the excitement which sharply defined personalities and attitudes can bring.... Not complaining, understand.... Sure, it is not everything we want, certainly not everything Matheson can do, but it’s still one of the best first drafts we’ve gotten in. (GR4-3)

|

Except that this particular “first” draft was Matheson’s second.

Justman too felt there was still much work to do. The same day Roddenberry’s memo hit, he wrote a long one of his own, complaining to John Black:

Justman too felt there was still much work to do. The same day Roddenberry’s memo hit, he wrote a long one of his own, complaining to John Black:

|

On the first page of the teaser, do we need to establish sixteen crew members down on the surface of the planet? Five lives are important too. Sixteen lives are more than I feel we can afford for this segment.... On page 45, McCoy’s second speech is schmucko. I don’t think “half of Kirk’s cellular structure is missing” or “half his blood.” I just think the poor fella is emotionally deprived.... Someday I hope to be able to write memos that are full of sweetness and light, and optimism, and faith and hope and charity and all the other chozzerai -- Yiddish for “crap” -- that I have been unable to corral up to now. I really do like to be a happy individual. Maybe I’m in the wrong business? Maybe I’ll just raise chickens. (RJ4-3)

|

John D.F. was less critical and becoming bothered that Roddenberry “couldn’t keep his hands off the scripts,” especially when those scripts had been written by sci-fi legends like Jerry Sohl and Richard Matheson. He later said, “In [Matheson’s] case... he really wanted to make his own fight with GR, and could do it. He was a professional. I know he had a talk about the final draft in GR’s office. I was there. He understood what the show was. He knew what we were doing. He tuned in immediately. So it was difficult for GR to make any kind of real arguments about structure. He had some bitches about where the story turned here and there, but, by and large, [‘The Enemy Within’] was one of the easy ones.” (17-4)

Or perhaps not. Matheson was already on draft number three of his teleplay, to be turned in on May 31 with a clear message to Roddenberry. On the title page, he didn’t type “2nd Draft,” but, instead, sought closure with two simple words: “Final Draft.”

Beyond the issues of screen credits and residuals, the magnitude of the work being done by the freelance writers on Star Trek was out of proportion to the money paid. The volume of the workload expected at Star Trek was unprecedented, with writers often receiving dozens of pages of notes from the producer on each and every draft, requiring more than mere script polishing but complete overhauling of their teleplays. What would be two weeks’ work on most other shows almost always became -- for the same money -- a full month’s work on Star Trek. This obsessive rewriting helped to make a TV classic but left in its wake many bruised egos, aborted writing assignments and irreparably damaged producer/writer relationships.

With the new draft in hand, Robert Justman sent another lengthy memo to John Black concerning production problems in filming the script as written, as well as inconsistencies with ship’s characters and the working of the Enterprise, as established in “The Corbomite Maneuver” and “Mudd’s Women.” These included Matheson calling for doors on the ship to be ajar and a description of Kirk splashing his face with water while in his cabin. The doors on the Enterprise, of course, slide open and shut and would never be left ajar. As to splashing water onto the face, Justman wrote to Black, “We have no provisions for a bathroom or a fire hydrant.” He closed, writing:

Or perhaps not. Matheson was already on draft number three of his teleplay, to be turned in on May 31 with a clear message to Roddenberry. On the title page, he didn’t type “2nd Draft,” but, instead, sought closure with two simple words: “Final Draft.”

Beyond the issues of screen credits and residuals, the magnitude of the work being done by the freelance writers on Star Trek was out of proportion to the money paid. The volume of the workload expected at Star Trek was unprecedented, with writers often receiving dozens of pages of notes from the producer on each and every draft, requiring more than mere script polishing but complete overhauling of their teleplays. What would be two weeks’ work on most other shows almost always became -- for the same money -- a full month’s work on Star Trek. This obsessive rewriting helped to make a TV classic but left in its wake many bruised egos, aborted writing assignments and irreparably damaged producer/writer relationships.

With the new draft in hand, Robert Justman sent another lengthy memo to John Black concerning production problems in filming the script as written, as well as inconsistencies with ship’s characters and the working of the Enterprise, as established in “The Corbomite Maneuver” and “Mudd’s Women.” These included Matheson calling for doors on the ship to be ajar and a description of Kirk splashing his face with water while in his cabin. The doors on the Enterprise, of course, slide open and shut and would never be left ajar. As to splashing water onto the face, Justman wrote to Black, “We have no provisions for a bathroom or a fire hydrant.” He closed, writing:

|

John, I think it is important enough, since this is supposedly our third show to shoot and we are starting our second one in the morning, that we get right to work on the revisions of this screenplay as fast as possible. I don’t know if Dick Matheson will be able to accomplish everything we need done in the amount of time we have left to get it done.... This script is not too feasible in its present state and I don’t think we have anything else that is more ready than this one. (RJ4-4)

|

Black rolled up his sleeves and did a script polish. He was careful to confine his changes to those that pertained to character traits of the series regulars and the workings of the Enterprise. He did not want to lose Richard Matheson’s distinctive voice -- that certain something that stamped this work as coming from a science fiction master.

|

Roddenberry did a rewrite of his own two days later, creating the June 8 Final Draft. Among the changes, he replaced crewman North with helmsman Sulu as ranking officer among the men left behind, and put more emphasis on this B-story and more personal anguish onto the “good Kirk” over his inability to find a way to save his landing team. It was this draft that was the first to be sent to the network and be distributed to cast and crew.

Leonard Nimoy was enthusiastic about the script. Nonetheless, he had some issues, and it was here where Nimoy began giving script notes -- something seldom allowed for in television production of the time. His letter to Roddenberry began: |

|

Gene, I hope you won’t mind my dropping some notes on “The Enemy Within.” Generally, I feel it is the best material we have had so far, and I will not dwell on the things I like but rather on some of the areas which struck me as problematic. (LN4)

|

Among them, Nimoy was bothered by the antagonistic relationship between Spock and McCoy. He complained that it “borders on open hostility.” He continued:

|

Also, it comes at a time when the Captain is in trouble, and the bickering in scenes 18 and 19 reduces two military men to a pair of children arguing over who should do the errand for mommy. (LN4)

|

Time would prove Nimoy wrong; the fans of Star Trek came to love the Spock/McCoy feud. For this story, in particular, the “bickering” helps to visualize much of Kirk’s growing inner conflict. However, the character conflict in this draft of the script needed -- and would receive - some refinement.

The next day, a memo arrived from Stan Robertson at NBC. He was perturbed over not having been shown the script until now. He wrote:

The next day, a memo arrived from Stan Robertson at NBC. He was perturbed over not having been shown the script until now. He wrote:

|

Quite honestly, Gene, our approval of this script is given very reluctantly since we feel that the major point which we objected to in the outline is more prominently apparent in the script. And that is what the characterization of Kirk’s “Alter Ego,” as portrayed, might do to the viewer’s image of our hero. (ST4-2)

|

Robertson recommended that the episode be pushed back on the NBC broadcast schedule so as to not alienate audience members tuning in for the first time.

Roddenberry made additional script changes, with revised pages coming in on June 11 and, even after production began, on June 15. It was Roddenberry who added the tidy conclusion to the confrontation on the bridge, with evil Kirk falling apart and seeking the embrace of the good Kirk. (In Matheson’s script, Kirk had knocked his evil self out with a phaser set on stun.) Despite the screen credit (acknowledging only Matheson as the writer), the script was now a collaborative endeavor.

Roddenberry made additional script changes, with revised pages coming in on June 11 and, even after production began, on June 15. It was Roddenberry who added the tidy conclusion to the confrontation on the bridge, with evil Kirk falling apart and seeking the embrace of the good Kirk. (In Matheson’s script, Kirk had knocked his evil self out with a phaser set on stun.) Despite the screen credit (acknowledging only Matheson as the writer), the script was now a collaborative endeavor.

“This is going to be the bible to Star Trek® and how it was made.

This is a book that I’m going to keep near and dear and utilize

through my life.” - Rod Roddenberry

This is a book that I’m going to keep near and dear and utilize

through my life.” - Rod Roddenberry

"I had to force myself to close [These are the Voyages, TOS, Season One]. Wow! It would be a bargain at ten times your set price. Fans the world over will be making comments of gratitude for years to come." - Curtis Fox startrekpeople.com.