- Home

-

Books

- When You Step Upon a Star

- Swords, Starships & Superheroes: From Star Trek to Xena to Hercules...

- Beaming Up and Getting Off - Life Before and Beyond Star Trek

- These Are the Voyages: Gene Roddenberry and the 1970s

- Long Distance Voyagers: Moody Blues >

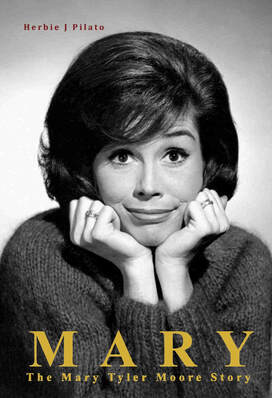

- MARY - The Mary Tyler Moore Story

- These Are the Voyages: The Original Series >

- Audiobooks/Movies

- Authors

- About Us

- Events/News

- Store

The iron-willed, strong-minded, and compassionate Mary Tyler Moore hailed from a family whose history was immersed in military and rigid rules. Although she was none too pleased that her ancestors mostly made their mark in war, it’s a legacy that prepared her for battles of her own – some of which she lost, in some of which she prevailed – all of which she confronted head-on. With creative differences at work or at home, the actress, the businesswoman, the philanthropist, the human being, throughout her life and career never backed away from a challenge. When conflicts arose she confronted each accordingly, whether personal, professional, emotional, psychological, or physical. She considered none as obstacles but rather par for the course, and never felt sorry for herself, no doubt because she hailed from that sturdy stock.

For years, Mary would speak of her alleged link to Captain John Moore, to whom she several times referred as a distant relative who stowed away to America from England, circa 1765, on an importing tea ship. But according to genealogist James Pylant, there are several “stowaway to America” stories that are commonly repeated but remain unproven. “Mary was given some incorrect information about her ancestry,” Pylant said diplomatically.

The more clearly defined and documented family line involved Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Tilghman Moore, a commander of the 4th Virginia Infantry in the Confederate Army, who purchased a Gothic Revival home in Winchester, Virginia. He offered it as the headquarters for Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Jackson resided four months in that home (today known as Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters Museum). Lieutenant Colonel Moore returned there, to the practice of law after being severely wounded at Manassas in 1861. He married Mary Fanny Bragonier, the daughter of Daniel George Bragonier, a noted minister of the German Reformed Church. Fanny’s mother, Mary E. (Shindler) Bragonier, whose family name was originally spelled Schindler, was the great-granddaughter of George Conrad Schindler of Wuerttemberg, Germany. He arrived in America at the Port of Philadelphia in 1752.

According to historian and author A.D. Kenamond, Schindler, a Revolutionary War soldier, apparently made a copper kettle for Martha Washington that was later on display at Valley Forge. In 1872, Lt. Col. Moore and Fanny welcomed a son, George Melville Moore. He later moved to New York, where he worked as a treasurer for an electric company, and married Anna Veronica Tyler, a native of that state. Their son, George Tyler Moore, known by his middle name (and his mother’s maiden name – a family tradition), was born in 1913 in Brooklyn and, due to his father’s well-paying job, attended private schools. Like his father, Tyler was later employed as a clerk by an electric company (by then alternately known as Consolidated Edison, Con Edison, or Con Ed) in New York.

In that same city, on January 24, 1936, Tyler, a Catholic, secured a marriage license with Marjorie Hackett, a Protestant who converted to Catholicism. On December 29, 1936, in the upscale suburb of Brooklyn Heights, their daughter Mary Tyler Moore was born. Her middle name continued the family tradition of utilizing the paternal grandmother’s maiden moniker. She arrived shortly before World War II began, near the end of the Depression, and nine years after television was created, when America and the world were ready to smile again. Comedian Milton Berle, who made his name in Vaudeville and later, as “Mr. Television,” the star of NBC-TV’s Texaco Star Theatre from 1948 to 1956, helped shape the small-screen medium which would give Mary, who would later become his friend, a career. “The day Mary Tyler Moore was born,” Berle would observe, “…the world became a better place.”

In many of her earliest days that followed, Mary attended St. Rose of Lima Catholic School in Brooklyn. In time, she became the eldest of three siblings, presiding over her brother John Hackett Moore (born 1944), and a sister Elizabeth Ann Moore (born 1956), who also received a Catholic education. According to The Real Mary Tyler Moore by Chris Bryars, their mother Marjorie said Mary was one of “three only children,” because they were born 36 months apart. Marjorie called Mary “…a pain in the neck to raise” due to her child’s fervent desire to dance and act. With no clear life or career direction of her own, Marjorie stayed home, while George, like his father before him, continued to work diligently in New York.

An average student in elementary school, Mary was shy in the classroom at St. Rose’s, but let loose upon hearing the day’s final school bell ring. She’d pester her cousins, who resided close by, into presenting shows in her backyard. “Even then I was frantic to become a performer,” she told Bryars. By no means wealthy, her family lacked for nothing beyond currency. In a videotaped conversation that was conducted by filmmaker Carlos Ferrer, Mary related that her father had said she was born in the “impoverished nobility” of Brooklyn Heights. When Mary was 4 years old, the Moore family relocated to larger quarters in Flushing, only to return to the Flatbush area on 491 Ocean Parkway two years later. For an interview with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Mary later described her neighborhood as made of homes with tree-lined front yards. “Some people had Fords or Hudsons. But everyone took the elevated train when they traveled to Manhattan to catch live shows or the latest movie and stage show at Radio City Music Hall.”

The New York Times later observed, “Mary Tyler Moore may not quite rank with Pee Wee Reese, the old Dodger shortstop, as a symbol of Brooklyn,” but the organizers of “Welcome Back to Brooklyn Day” eventually dubbed her Homecoming Queen. In her defense, the adult Mary sent a scathing letter to the editor, detailing a core portion of her early childhood:

For years, Mary would speak of her alleged link to Captain John Moore, to whom she several times referred as a distant relative who stowed away to America from England, circa 1765, on an importing tea ship. But according to genealogist James Pylant, there are several “stowaway to America” stories that are commonly repeated but remain unproven. “Mary was given some incorrect information about her ancestry,” Pylant said diplomatically.

The more clearly defined and documented family line involved Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Tilghman Moore, a commander of the 4th Virginia Infantry in the Confederate Army, who purchased a Gothic Revival home in Winchester, Virginia. He offered it as the headquarters for Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Jackson resided four months in that home (today known as Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters Museum). Lieutenant Colonel Moore returned there, to the practice of law after being severely wounded at Manassas in 1861. He married Mary Fanny Bragonier, the daughter of Daniel George Bragonier, a noted minister of the German Reformed Church. Fanny’s mother, Mary E. (Shindler) Bragonier, whose family name was originally spelled Schindler, was the great-granddaughter of George Conrad Schindler of Wuerttemberg, Germany. He arrived in America at the Port of Philadelphia in 1752.

According to historian and author A.D. Kenamond, Schindler, a Revolutionary War soldier, apparently made a copper kettle for Martha Washington that was later on display at Valley Forge. In 1872, Lt. Col. Moore and Fanny welcomed a son, George Melville Moore. He later moved to New York, where he worked as a treasurer for an electric company, and married Anna Veronica Tyler, a native of that state. Their son, George Tyler Moore, known by his middle name (and his mother’s maiden name – a family tradition), was born in 1913 in Brooklyn and, due to his father’s well-paying job, attended private schools. Like his father, Tyler was later employed as a clerk by an electric company (by then alternately known as Consolidated Edison, Con Edison, or Con Ed) in New York.

In that same city, on January 24, 1936, Tyler, a Catholic, secured a marriage license with Marjorie Hackett, a Protestant who converted to Catholicism. On December 29, 1936, in the upscale suburb of Brooklyn Heights, their daughter Mary Tyler Moore was born. Her middle name continued the family tradition of utilizing the paternal grandmother’s maiden moniker. She arrived shortly before World War II began, near the end of the Depression, and nine years after television was created, when America and the world were ready to smile again. Comedian Milton Berle, who made his name in Vaudeville and later, as “Mr. Television,” the star of NBC-TV’s Texaco Star Theatre from 1948 to 1956, helped shape the small-screen medium which would give Mary, who would later become his friend, a career. “The day Mary Tyler Moore was born,” Berle would observe, “…the world became a better place.”

In many of her earliest days that followed, Mary attended St. Rose of Lima Catholic School in Brooklyn. In time, she became the eldest of three siblings, presiding over her brother John Hackett Moore (born 1944), and a sister Elizabeth Ann Moore (born 1956), who also received a Catholic education. According to The Real Mary Tyler Moore by Chris Bryars, their mother Marjorie said Mary was one of “three only children,” because they were born 36 months apart. Marjorie called Mary “…a pain in the neck to raise” due to her child’s fervent desire to dance and act. With no clear life or career direction of her own, Marjorie stayed home, while George, like his father before him, continued to work diligently in New York.

An average student in elementary school, Mary was shy in the classroom at St. Rose’s, but let loose upon hearing the day’s final school bell ring. She’d pester her cousins, who resided close by, into presenting shows in her backyard. “Even then I was frantic to become a performer,” she told Bryars. By no means wealthy, her family lacked for nothing beyond currency. In a videotaped conversation that was conducted by filmmaker Carlos Ferrer, Mary related that her father had said she was born in the “impoverished nobility” of Brooklyn Heights. When Mary was 4 years old, the Moore family relocated to larger quarters in Flushing, only to return to the Flatbush area on 491 Ocean Parkway two years later. For an interview with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Mary later described her neighborhood as made of homes with tree-lined front yards. “Some people had Fords or Hudsons. But everyone took the elevated train when they traveled to Manhattan to catch live shows or the latest movie and stage show at Radio City Music Hall.”

The New York Times later observed, “Mary Tyler Moore may not quite rank with Pee Wee Reese, the old Dodger shortstop, as a symbol of Brooklyn,” but the organizers of “Welcome Back to Brooklyn Day” eventually dubbed her Homecoming Queen. In her defense, the adult Mary sent a scathing letter to the editor, detailing a core portion of her early childhood:

|

I was more than a little resentful of the suggestion in your article that I was an inappropriate choice to reign as Queen for “Welcome Back to Brooklyn Day” on June 9 [1996] (anyway, I thought I was to be King). Regardless of my worthiness, it does seem to me that “type” should play no part in this warm-spirited ceremony. One wonders what your greatest concern is – am I not funny enough? I can slip on a banana peel with the best of them.

I was born in Brooklyn Heights in 1936, where we lived for a short time before moving to Flushing. When I was 6 we returned, this time to Ocean Parkway in Flatbush. It was in this neighborhood that I lived for the next three years, learning much about the spirit that produces laughter, fear, anger and – last and above all – tolerance. The Moores and one other family were the only Catholics in an Orthodox Jewish community where my grandfather owned the house that we would live in. I made my first Communion at St. Rose of Lima Church and took no small amount of kidding for the bride-like veil I wore on that particular Sunday. “Well, so are you married to God now?” “No, stupid. How come you can’t touch money sometimes? And what’s the big deal about sundown?” We never let each other forget our differences, fistfights being a regular part of our activities. I don’t think I was without a bruise or scraped knees for the whole time we lived there. Nor were some of them. But I remember feeling that whatever the bullying, we also had fun. We knew we were struggling with more than childhood’s fight for supremacy and territory. There were differences that could have been given indelible names but weren’t. Instead, we found ourselves and we found ourselves to be friends. |

It’s that kind of intelligence, and well, “spunk,” that was part of Mary’s appeal. That descriptive word was spoken by Ed Asner as Lou Grant to Mary Richards in “Love Is All Around,” the pilot episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. But this combination of smarts, courage, and comedy played an important part throughout Mary’s life, even before she began her career. She said her parents blessed her with an appreciation for humor. They made her think and feel what’s funny, while Mary learned to welcome the laughter in others – though not as a class clown, which she never wanted or tried to be. Her parents may not have had money, but they both majored in English in college, and taught her how to speak correctly.

“We never wanted for anything,” Mary said. “We never went hungry. There weren’t a lot of luxuries,” but dancing lessons were arranged when Mary wanted them. Although proud of her Brooklyn influences, as were and remain many celebrities born in that historically rich and cultural place, in time she sought to leave it all behind.

“We never wanted for anything,” Mary said. “We never went hungry. There weren’t a lot of luxuries,” but dancing lessons were arranged when Mary wanted them. Although proud of her Brooklyn influences, as were and remain many celebrities born in that historically rich and cultural place, in time she sought to leave it all behind.

- Home

-

Books

- When You Step Upon a Star

- Swords, Starships & Superheroes: From Star Trek to Xena to Hercules...

- Beaming Up and Getting Off - Life Before and Beyond Star Trek

- These Are the Voyages: Gene Roddenberry and the 1970s

- Long Distance Voyagers: Moody Blues >

- MARY - The Mary Tyler Moore Story

- These Are the Voyages: The Original Series >

- Audiobooks/Movies

- Authors

- About Us

- Events/News

- Store